Letter from Our President

The nights are a little cooler, the days a little shorter, and the leaves on our birch trees are beginning to turn yellow. For most of us that means fall is coming and with it our North American hunting seasons are just around the corner.

If you are like me, fall means early mornings in the woods or upland fields. It means wood smoke coming from the stove in the tent, and the bustle of hunting partners getting gear ready to spend the day in the field. It matters not what you are hunting or how, it just matters that you are hunting.

The past year has been interesting to say the least. For some, business slowed or changed completely. For others, it meant cancelled trips and trying to navigate working and educating from home. But for all hunters and those who cherish the wild places it also meant we have a bunch of new folks taking to the field for the first time to try their hand at hunting. Millions of our neighbors became first-time gun owners and many are eagerly seeking training in the safe use of new firearms. Likewise, many are looking for a mentor to teach them the ways of the hunter and how to harvest their own game.

For 50 years SCI has been the leader in hunter advocacy. Not just nationally, or internationally, but in literally every state at some point. Without the unwavering stance that hunting and hunters are worth protecting and promoting, we would not enjoy the hunting opportunities we have today. We would not have the access to many of the places we love to hunt. We would not continue to enjoy the firearms freedoms we have today. Simply put, SCI is the leader in hunting advocacy and protection worldwide.

Your membership means you are part of a team of hunters who have gone above and beyond to help protect hunting and a way of life. Thank you.

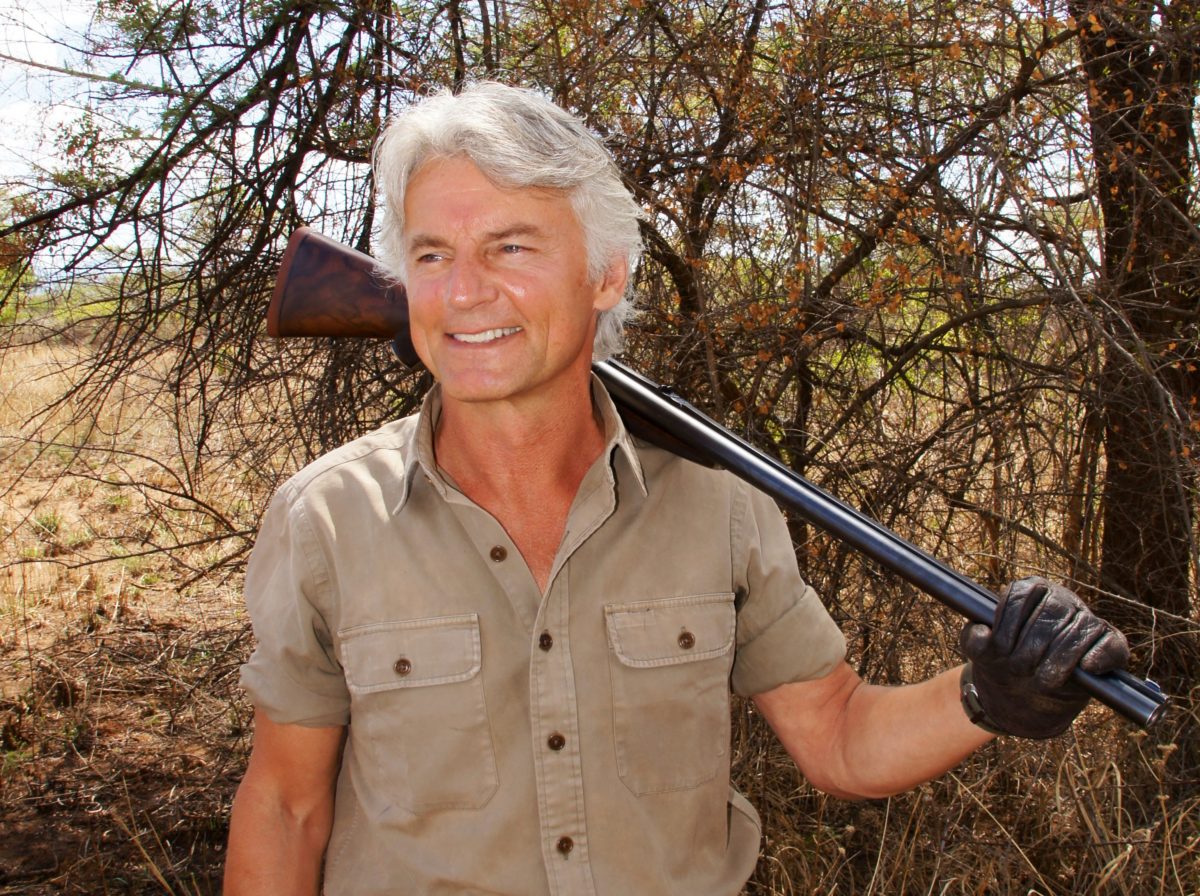

Locally, your Central Washington Chapter leadership is meeting live again and moving full speed toward what we hope is the best Annual Banquet ever. Mark your calendar for December 11th to join us live at the Yakima Convention Center for our 24th banquet. We have some special things planned for this year you will not want to miss! J Alain Smith of Rugged Expeditions will be joining us for the evening as our MC and will also host a Meet & Greet earlier in the afternoon. Alain is a fellow Washingtonian from Woodinville and is a long-time SCI supporter and a Weatherby Conservation Award Winner. If you have not had the pleasure of meeting Alain, you will not want to miss his wit, his energy, and his message about the importance of SCI. John Nelson will be joining us again as our auctioneer and working with Ted Beach as our lead Spotter for the live auction. Finally, we are working on a one-time-only auction item that will get the heart racing for every hunter. Stay tuned as the details are worked out, because if this project becomes reality, you won’t want to miss your opportunity to be in on the bidding.

Watch your email and mailbox for registration details. I also encourage you to check out our ever changing website and Facebook page for updates, auction items, and online registration. Thanks for being a hunter and supporter of SCI and the Central Washington Chapter. I look forward to seeing you in December!

Randy Bauman

President – SCI Central Washington Chapter

Annual Banquet & Conversation Fundraiser

December 11th 2021 – Yakima Convention Center

Special guest and emcee, J. Alain Smith or Rugged Expeditions – Hunter, Writer, Musician, Adventurer

https://jalainsmith.com/

40 Special VIP Tickets Available

This ticket gets you into a special meet and greet with Alain Smith from 2-4pm Saturday afternoon at the convention center. VIP tickets include banquet entry.

DINNER. GAMES. RAFFLES. LIVE AUCTION. SILENT AUCTION.

Doors open at 4pm, Dinner at 6pm

PLEASE HELP! Peter the Pug is looking for donations for our fundraiser.

Gift certificates, hunts, fishing trips, silent auction items, homemade items and more are always appreciated – be creative!

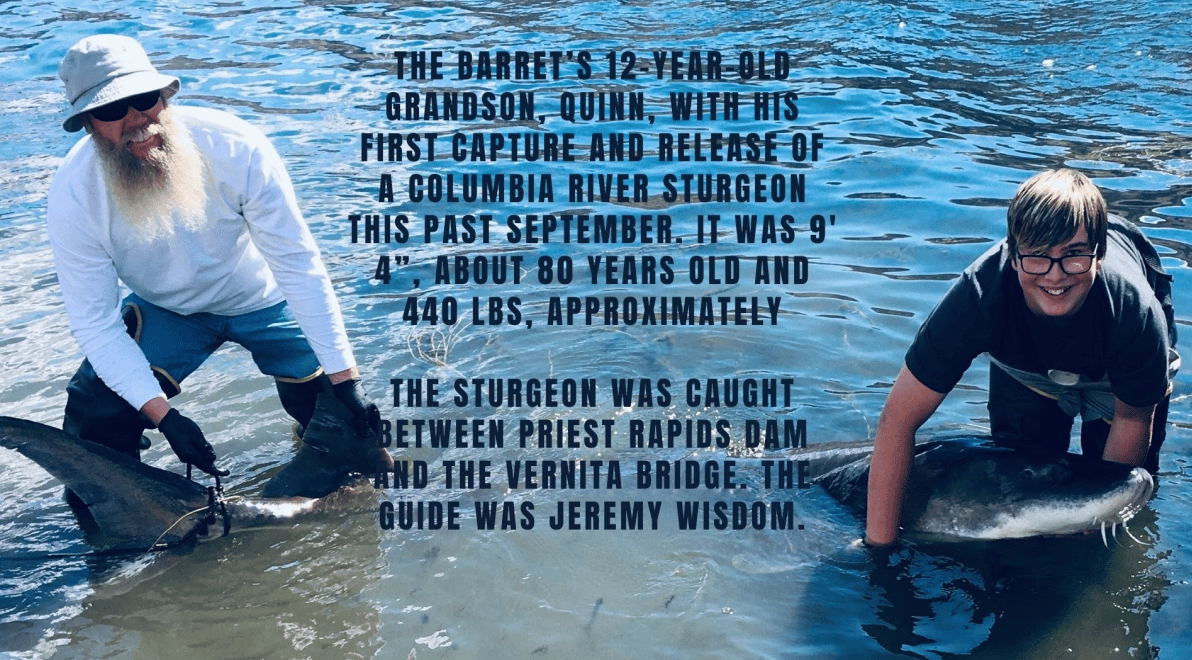

Making Memories

RECIPE: Bison Taco Meat

Ingredients

- 1 lb bison burger

- 1 medium onion, chopped

- 2 cloves garlic, pressed

- 1 1/2 tsp chili powder

- 1/2 tsp oregano

- 1/2 tsp paprika

- 1/4 tsp cumin

- 1/4 tsp black pepper

- 1/2 cup tomato sauce

- 2 tsp worcestershire sauce

Directions

- Crumble bison into frying pan over medium-high heat.

- Add chopped onion and garlic, cooking until meat is browned and onions are soft.

- Stir in spices.

- Add tomato sauce and worcestershire sauce and simmer until thickened or browned to your liking.

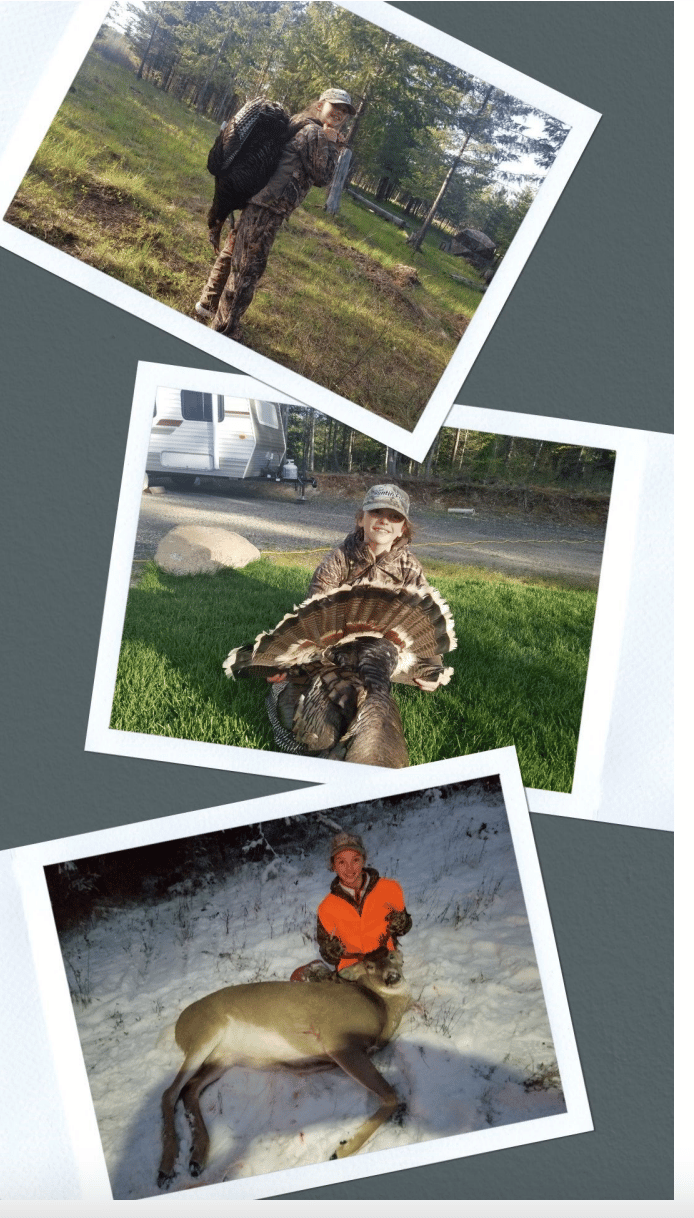

My daughter has been involved with my personal hunting and guide business for as long as she can remember. She always wanted her own opportunities to hunt, but had to wait to pass hunters safety.

Well, this year she checked that box and started on her own adventures.

This spring she was able to punch her first tag on a nice mature gobbler at 10 yards! As the summer went on ,we spent a lot of time shooting and practicing for her upcoming first big game hunt.

We put in our share of scouting and found the perfect spot for her first hunt. After only an hour in the blind, she was able to harvest her first deer with a perfect shot. Now she is totally hooked and ready to go hunt the ‘big’ animals.

– Ty Brown

Botswana Lion Hunt

by Glenn Rasmussen

August 1986

We had found fresh lion tracks while stalking the small zebra herd. Suddenly, the zebras bolted and ran. John Northcote, our professional hunter and guide, and the trackers immediately became alert. Glassing the small openings in the monopani forest, John spotted a lioness. She was laying partially concealed next to some thorn brush several hundred yards away. He turned to me and said, “I’ll bet she has a boyfriend nearby.” Scanning the thorn brush, John spotted a second lion asleep, a magnificent male with a big, dark, reddish mane. A quick glimpse of the sleeping lion and we knew he was the one we had come to Africa for.

Dropping to our hands and knees, we backed out of the low brush we were in. We could move into a fringe of timber and use the trees and ant hills as cover. We had a perfect set up and could approach within 50 yards of the male lion. Halfway through our stalk, the only vehicle we encountered in the forest rumbled down a deserted road, scaring the lions into the forest. Worst of all, it was another hunting guide crossing through an area he was not supposed to be in.

John was seething, my son, Eric was ticked off, and I was silently cursing to myself. John huddled with Metsi and Tadu, the trackers. The direction the lion was running would lead him to a road about 300 yards into the forest. We set off at a fast walk to try to catch him crossing the road. After walking 200 yards Metsi spotted the lion running off to our right. We ran to high ground for a better view, but could not see him because of the dense undergrowth. All of us ran towards the road, hoping to see the lion.

This was an exceptional lion with a great red mane, and John, our hunting guide, wanted us to get him. As we reached the road, I went through a mental checklist of what I needed to do to be ready. Eighty yards in front of us, the lion crossed the road at a fast trot. “Get him” was all John said. Dropping to one knee, I squeezed off a quick shot with my .375 as the lion ran through the small opening. The shot hit the lion just inches behind the front left shoulder. He kept going, as John fired his .458, and I touched off a second. Neither of us hit him again. It was 5:30 p.m., and the sun set in 45 minutes, and we had a wounded 500-pound lion in a dense thorn brush.

When my son, Eric, and I planned our safari to hunt Africa’s dangerous game we had spoken briefly about the dangers. Talking with my family before we left, I jokingly told them, “We’ll be gone about a month, unless we get eaten by a lion.” I didn’t realize how humorless that prospect would become.

We booked our safari jointly through Outdoor Specialists, Inc. of Plano, Texas, and African Safari Specialists of Bellevue, WA. We had selected a 21-day safari in Botswana with Hunter’s Africa. Our hunt would be conducted from three different camps, each offering a variety of game. Each of us wanted a lion, cape buffalo, sable and hoped to get one leopard between us. To select Hunter’s Africa, we had contacted several safari companies, spoken with half a dozen booking agents and met with three professional hunters. John Northcote and Hunter’s Africa’s operation had impressed us. They offered no guarantees, but came highly recommended and all of their references checked out. It was also possible to take other plains game and a sitatunga on the safari if the opportunity arose.

The reality that this hunt was going to be different hit us while we waited in our doctor’s office to get various inoculations required by Botswana. We were not going to be hunting elk in our home state of Washington, nor was I going to Montana on a sheep hunt. It would also be different from our plains game hunt to Southwest Africa three years earlier.

Together, we would be hunting cape buffalo, lion and

leopard, three dangerous game animals which have no

comparable counterparts on the North American

continent. It was exciting and sobering. From the

doctor’s office, we went directly to the shooting range

and began practice with our .375 and .300 Winchester.

I looked forward to hunting with my son, Eric.

He had matured into an excellent hunting partner for a

22-year-old college student. What I could not have

foreseen was that it would be Eric’s courage and

hunting instincts that would save us from mauling, or

worse, from a wounded lion.

We flew Pan American Airlines to London, then

boarded a British Airways flight to Harare,

Zimbabwe. From Harare, we flew to Victoria Falls

and were met by a representative from Hunter’s

Africa. A good night’s sleep and a view of Victoria

Falls did wonders for us, and we were ready to go the

next morning.

In Botswana, we met John Northcote, our

professional hunter and guide. John is one of the old

time East African hunters. He started hunting in

Kenya in 1948, and has hunted in Uganda, Tanzania,

Zimbabwe, Zambia and Botswana.

The first ten days of the safari went quickly,

but we had not found any lions. On the tenth day of

hunting, we changed camps. King’s Pool camp is one

of Hunter’s Africa’s best camps. It is located on the

Chobe River near the confluence of the Chobe and the

Kwando rivers. John was glad to be back on the

banks of the Chobe River. His spirits picked up and

somehow transferred the excitement to us. His actions

and skills in the field instilled a quiet confidence in a

hunter. Entering the new hunting area, we saw sable,

impala, zebra and fresh lion tracks. Our first night in

camp, John said that the hyenas and baboons were

barking and screeching at nearby lions and leopards.

We were up early, looking for fresh lion sign.

While scouting for lions, we came across a herd of 40

wildebeest. One had exceptionally wide inward

curving horns; John recommended Eric take it. Eric’s

shot was well placed, and the horns measured to

Roland and Ward standards. During the afternoon

hunt, we decided to try for a zebra. Just before dark,

while stalking a herd of zebra, John had sensed the

lion was near.

Our stalk on the reddish maned lion was

spoiled by the vehicle driving up. We were lucky to

catch up with the lion before he disappeared into the

forest. My shot should have been fatal to the lion, but

he had continued loping across the road and into the

trees. My second shot and John’s first had missed.

Now, with less than 45 minutes before sunset, we had

to track the wounded lion in heavy monopani forest.

Johns sent Metsi for the truck. If we could follow the

lion with the vehicle, all the better and safer. Once

into the Toyota and positioned to shoot, we proceeded

less than 100 yards before we could go no farther: too

many trees and thorn brush blocked the way. John got

us all out of the vehicle. At first, I was going to have

Eric stay in the vehicle, then John told him to come

with us and bring his .300 Winchester. Metsi carried a

shotgun he had once killed a leopard with at 10 feet,

and Tadu carried his machete.

John and Metsi followed the tracks and blood

trail cautiously. They carefully circled and sidestepped the thick brush. We had picked our way

about 200 yards when we were halted by a deep

terrifying growl 45 yards away. Quickly, we moved

to slightly higher ground on the side of an ant hill near

a large tree. Metsi lined Eric and me up in shooting

positions. John, then myself, and slightly behind me

and to my left were Eric and Metsi. John set his rifle

down and raised his binoculars to try to pick the lion

out of the shadows of the brush.

The charge came before John’s binoculars

reached his eyes. A blur of yellow preceded by a

deafening roar was nearly on us. I got off two shots,

one causing a flesh wound and the second a miss.

One of John’s shots dug a furrow inside one of the

lion’s legs, missing the bone and chest by two inches.

John’s third round jammed. The lion was almost on

us.

Eric had the only scoped rifle. He saw the

charge magnified in colors of brown and yellow, in

three distinct frames as he shot. Each frame lasted

approximately a second, and for each second, a shot

and automatic chambering off a new round. With

each round, he expected to see the lion go down, but it

did not. On round three, at 15 feet, all he could see

was the face. A face he describes as constricted with

the worst anger you have ever seen in anyone mad at

you in your life. His third shot blinded the lion’s left

eye and caused him to veer off and crash into a fallen

limb next to us.

The tree limb spun and knocked John down

and hit me in the legs. Metsi and Tadu were

screaming hysterically for us to shoot the lion amidst

us as it whirled, pawing at its eye. As the lion’s one

good eye focused on us, I shot the lion twice, and Eric

and John shot him once. The lion went down and,

unbelievably, came up again. I shot him through the

shoulder and he finally went down for good.

The size of the lion was overwhelming. It took four of

us lifting plus a winch to get the lion into the back of

the Toyota. The lion scored 25 and 11/16 SCI, using

the Safari Club International standards, which would

make him number 27 in the current record book.

Neither Eric or I were able to sleep that night, and both of us wondered when and if the knots would

leave our stomachs.

Our next challenge was to get a leopard. I had first shot on the lion, and now it was Eric’s turn. Our nerves were fried, as Eric described it, from the lion charge. For the next two days, we had guns to shoulder if a bird flushed. Early on the morning of the third day, John found where a leopard had killed a zebra. He was confident the leopard would return that night. Since it was early morning, he recommended we leave the area undisturbed during the day and return and build a blind by the zebra in the late afternoon. We still had a full day to hunt, and John asked me if I would like to try for a sitatunga. We went to the Chobe River and took out a special plat formed boat that Hunter’s Africa had moored at the edge of the great marshes. High winds immediately made hunting difficult at best. We were out about an hour and a half when we started back. On the way in, we spotted a sitatunga. John ran the boat into the reeds and cut the engine. From the raised platform on the boat, I could see where the sitatunga had disappeared.

It suddenly raised its head, giving me a good shot. With one shot, it went down. Tadu was out of the boat at the crack of the shot and retrieved the trophy. Luck was on our side. A fine male sitatunga, which just missed the SCI minimums. Hunters had planned safaris around taking a sitatunga, and I had taken one in less than two hours of hunting. John attributed it to pure coincidence and luck.

We were back in camp before noon. At 4:00 we headed out. Eric put bug goop on and changed into a long-sleeved shirt to protect him against bugs. We drove out to build the leopard blind. John laid out the blind to take advantage of the moon and the position of the zebra kill. A slot had been built into the blind so the gun could be placed with the scope sighted in on the kill. All Eric would have to do was to sight through the scope and pull the trigger. The cross hairs were set where the leopard would feed. John surprised us by taking five of us to the blind. We asked John why: it was simple. Leopards cannot count, and if a cat saw us go into the blind and come out, it might still come to the kill. Eric and John settled into the blind, and I returned to the Toyota with the trackers. I had just settled down to watch the African sunset when Eric’s rifle cracked. A record book leopard had come to the zebra kill within an hour. The first animal to come to the kill was a mongoose. Eric watched the mongoose feed on the zebra and lick his feet fastidiously. When the mongoose left, Eric sat back and heard something. John motioned him not to move. Then he heard the distinct sound of claws on the zebra. When he looked back through the scope, the leopard was on the kill. Mesmerized, Eric watched the leopard begin to eat. John tapped him on the shoulder and whispered, “Shoot him.” When Eric touched the trigger, the leopard died instantly. A giant male leopard that scored 15 6/16, which would make him number 43 in the current SCI record book. We were overjoyed and amazed. A world’s record class leopard for Eric, and a sitatunga for me in one day.

`With a lion and a leopard secured, we switched our attention to cape buffalo. During the first half of our hunt, we had concentrated on the cats and passed up several opportunities to track small herds of buffalo. The only other game we had taken was Eric’s sable. The first day of our hunt had been at the Jarwe camp. John had us up at 6:00 a.m. We ate a light breakfast and had our rifles sighted in by 7:00 a.m. Boarding John’s Toyota, we headed out of camp. Less than a quarter of a mile away, we stopped to check a water hole. John found fresh tracks of a lone sable bull. He had a short talk with his trackers and we headed to a second water hole. I spotted the outline of a large animal in the brush and pointed it out to John. It was the sable bull. John motioned to Eric to get out of the Toyota and they began a short stalk. Using thorn brush and ant hills for cover they stalked within 150 yards of the sable. Eric’s shot was true, and a regal sable with 42 inch horns and jet black mane was his. It was a great way to start off a hunt. Our luck at the Jarwe camp did not hold. We found a fresh elephant kill. Poachers had shot the bull elephant in Zimbabwe and tracked it into Botswana. They took the ivory and left the carcass to rot. We cut a path to it and set up a blind. If there were lions in the area, they should be drawn to this fresh kill. Not a lion showed for the next four days. Hunting settled into a routine of early rising, long days of hunting and to bed by 8:30 or 9:00 p.m. Eric described it as “an incredible feeling, kind of like a dream; you can’t believe you’re really there.” Yet the glassing of giraffes, zebra and warthogs, and the night sounds combined with the day’s conversation had formed the “feel” of hunting Africa. Now with only four days left to hunt, we were concentrating on buffalo. The previous day’s hunting had turned up two herds of buffalo, but none of the bulls in either herd were big. John assured us our luck would change. Today, Eric and I had stalked several herds of cape buffalo, but the opportunity to take a good bull did not present itself. Headed into camp, we cut fresh buffalo tracks. John stopped the Toyota and his trackers Metsi and Tadu jumped out, and motioned us to follow. The wind was wrong for a stalk, but John explained that once the herd spooked, we might have a chance at a second stalk. The herd moved off quickly as the wind blew our scent to them. We continued to follow them and soon had the wind in our favor. John had us move slower and more methodically. The herd of 40 to 60 buffalo was only 150 yards in front of us, but thick vegetation blocked our line of sight. Cautiously, we moved into position for a shot. A big bull with a very good boss and wide horns came into view. I steadied the .375 with John’s shooting sticks and waited for the bull to turn his head. The jacketed bullet hit just behind the shoulder blade. The buffalo jumped and ran to our right. I put another round through its chest and my third shot hit the heart. My first cape buffalo was dead. Standing next to it, I was impressed by its size and massive horns. The next day, we returned to where I shot my cape buffalo and Eric got one. We found the tracks of a small herd of buffalo. After an hour of tracking, we caught up with the herd of nine. John eased Eric within 50 yards of a record class bull. Eric’s first shot was low and missed the bull. The bull ran 20 yards and stopped. His next shot was a solid hit in the shoulder. Seriously wounded, the cape buffalo moved deep into the dense thorn brush of the forest. Silently, we followed John and Tadu, tracking the wounded animal. After zigzagging through a quarter of a mile of thick brush following the blood trail, John spotted the buffalo. He motioned Eric to shoot. John shot immediately after Eric did. The buffalo died instantly. John’s .458 and Eric’s .375 shots were less than two inches apart through the buffalo’s heart. John’s skill in tracking and a backup shot were well received by us. Wounded cape buffalo have killed guides and hunters alike. Our safari proved to us that highquality lion hunting does still exist in Botswana, and that it can be combined on a 21-day hunt with leopard and cape buffalo hunting. There can be breath taking and heart stopping moments defining new levels of excitement. Hunting can also be quiet and uneventful, but never boring. After waiting over a poacher’s elephant kill for four days where a lion should have been, it was apparent no guarantees could exist on taking a lion, much less a good maned one. Only steady hunting, the application of a professional hunter’s knowledge of his area and the game hunted, and some luck will make for a truly successful hunt. Like other hunters who are richer from their African experience, we hated to leave. Our safari was led by a man who represents a piece of African history in a land we had dreamed about as children. As Eric says, “It’s not just the hunt or the trophies. It’s seeing things no one else will ever see, experiencing the danger and living to share it with one’s family and friends.”